How

to

Write

Satire

A

Conversational

Guide

to

Humor

and

Irony

So,

you

want

to

write

satire?

Excellent

choice!

Satire

is

the

art

of

using

humor,

irony,

and

exaggeration

to

poke

fun

at

the

world’s

flaws

–

all

while

keeping

a

(mostly)

straight

face.

In

this

comprehensive

guide,

we’ll

walk

(and

joke)

you

through

everything

from

satire’s

ancient

origins

to

practical

writing

techniques,

step-by-step

crafting

advice,

common

formats,

ethical

do’s

and

don’ts,

and

even

some

exercises

to

flex

your

funny

bone.

Grab

your

wit

and

let’s

dive

in

–

with

a

grin

and

a

raised

eyebrow.

Understanding

Satire:

Humor

with

a

Purpose

Satire

isn’t

just

about

cracking

jokes;

it’s

humor

with

a

mission.

At

its

core,

satire

uses

laughter

as

a

weapon

(or

gentle

tickle)

to

expose

and

criticize

stupidity

or

vice

in

people,

organizations,

or

society.

Unlike

pure

comedy,

satire

always

has

a

target

or

message

–

it’s

“ha-ha”

with

a

side

of

“aha!”.

Consider

it

the

love

child

of

stand-up

comedy

and

journalism,

delivering

truth

wrapped

in

laughter.

-

It’s

critical:

Satire

holds

up

a

funhouse

mirror

to

real

issues,

reflecting

problems

in

a

distorted

way

so

we

can

see

them

clearly.

A

good

satirist

is

part

comedian,

part

social

critic. -

It’s

humorous:

Satire

leverages

irony,

sarcasm,

and

absurd

exaggeration.

Even

if

it’s

not

knee-slapping

funny,

it’s

witty

enough

to

sugarcoat

the

critique.

(Think

of

it

as

the

spoonful

of

sugar

that

makes

the

medicine

of

truth

go

down.) -

It’s

insightful:

The

goal

isn’t

just

laughs

–

it’s

to

spark

reflection.

Great

satire

leaves

you

thinking,

“Whoa,

that

silly

story

really

made

a

point

about

[insert

societal

issue].” -

It’s

timely:

Satire

often

tackles

current

events

or

cultural

trends.

Hitting

a

moving

target

–

say,

the

latest

political

gaffe

or

viral

craze

–

makes

the

satire

punchier

and

more

relevant.

Importantly,

satire

is

not

just

goofing

off.

It’s

not

a

mere

string

of

jokes,

and

it’s

definitely

not

cruelty

masquerading

as

humor.

Satire

isn’t

just

parody

(though

it

often

uses

parody),

and

it

isn’t

a

license

to

bully.

A

satirical

piece

usually

has

a

perspective

(often

a

moral

stance

or

plea

for

sense)

behind

the

punchlines.

If

pure

comedy’s

only

aim

is

to

amuse,

satire’s

aim

is

to

amuse

and

critique.

Example:

One

of

The

Onion’s

classic

headlines

reads,

“World

Death

Rate

Holding

Steady

at

100

Percent.”.

It’s

deadpan,

it’s

absurd

–

and

it

slyly

mocks

how

news

media

report

the

obvious

as

if

it’s

breaking

news.

The

humor

makes

you

chuckle,

but

the

insight

(that

death

is

inevitable

–

shocker!)

makes

you

think

about

media

sensationalism.

In

short,

satire

lives

at

the

intersection

of

funny

and

fiery.

It’s

the

stand-up

comic

who

makes

you

laugh

and

reconsider

your

opinions.

As

the

saying

(often

attributed

to

George

Bernard

Shaw)

goes,

“If

you’re

going

to

tell

people

the

truth,

you’d

better

make

them

laugh

or

they’ll

kill

you.”

Satire

does

exactly

that

–

deliver

truth

disguised

as

jest

–

and

in

the

process,

ideally,

makes

the

truth

a

bit

easier

to

swallow.

A

(Very)

Brief

History

of

Satire

Ever

wonder

who

thought

making

fun

of

powerful

people

was

a

good

idea?

(A

brave

soul,

that’s

who.)

Satire

has

deep

roots

–

it’s

been

around

at

least

since

ancient

Greece,

proving

that

humanity’s

been

rolling

its

eyes

at

authority

for

millennia.

-

Ancient

origins:

The

term

satire

comes

from

the

Latin

satura,

meaning

a

“mixed

dish”

or

medley.

Early

Roman

satire

was

indeed

a

mixed

platter

of

prose

and

poetry

aimed

at

social

criticism.

But

even

before

the

Romans,

the

Greeks

were

at

it:

Aristophanes,

a

playwright

in

5th-century

BCE

Athens,

wrote

comedies

like

Lysistrata

that

used

outrageous

scenarios

(women

on

a

sex

strike

to

force

men

to

end

a

war)

to

lampoon

the

politics

of

the

day.

The

idea

that

humor

can

confront

serious

issues

was

already

born

–

women

denying

sex

for

peace

is

absurdly

funny

and

a

pointed

critique

of

war-making. -

The

Roman

trio

–

Horace,

Juvenal,

Menippus:

Fast

forward

to

ancient

Rome,

where

satire

fully

blossomed

as

a

literary

form.

Horace

(65–8

BCE)

and

Juvenal

(1st–2nd

c.

CE)

wrote

very

different

styles

of

satire

that

still

define

the

genre

today.

Horatian

satire

(named

after

Horace)

is

gentle,

playful,

and

urbane

–

it

ridicules

universal

human

follies

with

a

wink

and

a

nudge.

Think

of

it

as

a

friendly

roast

that

says

“we’re

all

fools

sometimes.”

Juvenalian

satire

(from

Juvenal),

on

the

other

hand,

is

anything

but

gentle

–

it’s

biting,

angry,

and

not

afraid

to

name

names.

Juvenal

went

for

the

jugular,

attacking

the

corrupt

elites

of

Rome

with

scathing

moral

outrage.

(If

Horace

is

Jon

Stewart,

Juvenal

is

John

Oliver

on

a

really

bad

day.)

There

was

also

Menippean

satire

(from

Menippus

of

Greece),

a

more

rhapsodic,

mixed-form

satire

that

often

targets

mindsets

or

philosophies

rather

than

specific

people

–

using

absurd

characters

and

plots

to

ridicule

certain

attitudes

or

ideas.

These

three

styles

–

Horatian

(light-hearted

chuckles),

Juvenalian

(incensed

rants),

and

Menippean

(fantastical

spoofs

of

ways

of

thinking)

–

still

inform

how

we

categorize

satire

today. -

Medieval

mischief

and

Renaissance

wit:

In

the

Middle

Ages,

satire

survived

in

fables,

folklore,

and

the

jabs

of

court

jesters.

By

the

Renaissance,

it

regained

literary

respectability.

Dante

and

Chaucer

included

satirical

barbs

in

their

works.

Erasmus

wrote

In

Praise

of

Folly

(1509),

a

wry

essay

that

satirized

the

Church

by

sarcastically

praising

foolishness.

The

idea

of

using

a

fake

persona

–

in

Erasmus’s

case,

a

personification

of

Folly

–

to

speak

truths

ironically

became

a

common

satirical

device. -

Swift,

Twain

&

the

rise

of

modern

satire:

Satire

really

hit

its

stride

in

the

18th

and

19th

centuries.

Perhaps

the

most

infamous

classic

satirist,

Jonathan

Swift,

shocked

the

world

with

A

Modest

Proposal

(1729).

Writing

in

the

voice

of

a

calm

economist,

Swift

earnestly

“proposed”

that

the

impoverished

Irish

might

ease

their

woes

by

selling

their

babies

as

food

to

rich

gentlemen

and

ladies.

😳

This

horrifying

suggestion

was

of

course

satirical

–

Swift’s

over-the-top

exaggeration

was

meant

to

highlight

and

condemn

the

cruel

neglect

of

Ireland’s

poor

by

the

English

government.

It

was

Juvenalian

satire

at

its

finest:

outrageous

and

no-holds-barred,

yet

undeniably

effective.

Readers

were

aghast

–

and

then,

if

they

understood

the

irony,

deeply

moved

by

the

real

message.

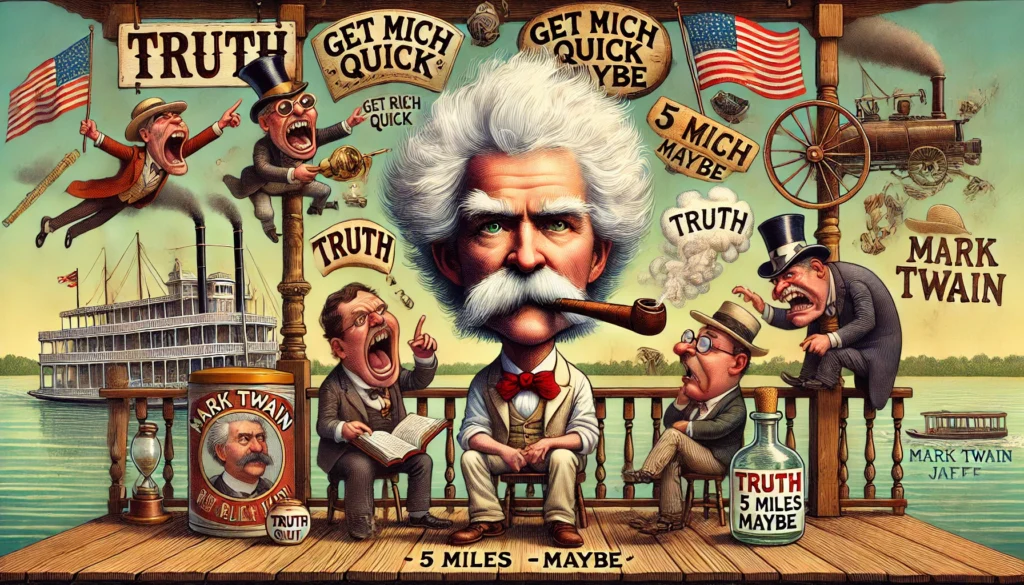

Mark

Twain’s

wry

expression

here

says

it

all

–

he’s

about

to

drop

a

satirical

quip.

Twain’s

humor

skewered

the

absurdities

of

American

life.

By

the

19th

century,

satire

found

a

home

in

American

literature

through

the

pen

of

Mark

Twain.

Twain’s

novels

and

essays

–

from

the

sharply

funny

travelogue

The

Innocents

Abroad

to

the

enduring

Adventures

of

Huckleberry

Finn

–

exposed

hypocrisy

and

absurdity

in

society

with

Horatian

wit.

Twain

often

took

a

“wise

fool”

perspective:

a

naïve

narrator

(like

young

Huck

Finn)

who

innocently

points

out

the

contradictions

of

adult

society.

This

technique

let

Twain

tackle

heavy

topics

(slavery,

greed,

pretentiousness)

with

humor

and

a

light

touch.

He’s

also

famous

for

snappy

satirical

one-liners.

For

example,

Twain

advised,

“Get

your

facts

first,

then

you

can

distort

them

as

much

as

you

please.”

In

one

swoop,

he

both

mocks

dishonest

journalists

and

gives

a

tongue-in-cheek

tip

about

satire

–

know

the

truth,

then

exaggerate

it.

-

20th

century

to

today:

In

the

modern

era,

satire

is

everywhere

–

in

print,

on

stage,

on

air,

online.

The

20th

century

saw

satire

thriving

in

essays

(think

Dorothy

Parker’s

acid

wit

or

George

Orwell’s

allegorical

Animal

Farm),

in

theater

(e.g.,

Oscar

Wilde’s

social

comedies),

and

especially

in

political

cartoons.

In

the

21st

century,

satire

exploded

on

television

and

the

internet.

Shows

like

Saturday

Night

Live

and

The

Daily

Show

use

sketch

and

news-parody

formats

to

instantly

react

to

current

events.

Stephen

Colbert,

for

instance,

famously

adopted

a

satirical

persona

as

a

pompous

conservative

pundit

on

The

Colbert

Report

–

by

“playing

a

character”

he

parodied

media

bias

and

political

spin,

all

while

(in

character)

pretending

not

to

be

joking.

And

of

course,

digital

media

has

its

satirical

kings:

The

Onion,

born

as

a

college

newspaper

in

1988,

set

the

standard

for

news

satire

with

headlines

that

are

sometimes

so

on-point

people

mistake

them

for

real

news.

(Case

in

point:

China’s

Beijing

Evening

News

reprinted

an

Onion

story

about

Congress

threatening

to

move

out

of

D.C.

without

realizing

it

was

satire

–

oops!)

Through

the

ages,

the

targets

and

styles

of

satire

have

evolved

–

from

ancient

politicians

in

togas

to

modern

celebs

on

Twitter

–

but

the

essence

remains:

satirists

use

humor

to

speak

truth

to

power

(or

to

stupidity).

Understanding

this

lineage

isn’t

just

trivia;

it

reminds

you

that

when

you

write

satire,

you’re

joining

a

grand

tradition

of

noble

smart-alecks.

Techniques

of

Satire:

Your

Toolkit

of

Tricks

Writing

satire

is

like

doing

magic

with

words

–

you

misdirect,

dazzle,

and

sometimes

shock

the

audience

to

make

a

point.

To

craft

effective

satire,

you’ll

want

to

master

a

few

trusty

techniques.

Here

are

the

big

ones

in

the

satirist’s

toolkit

and

how

to

use

them:

Irony

(and

Sarcasm)

Irony

is

the

lifeblood

of

satire.

In

simple

terms,

irony

means

saying

the

opposite

of

what

you

really

mean,

or

highlighting

a

gap

between

expectation

and

reality.

It’s

the

wink

that

says,

“I’m

saying

this,

but

you

and

I

both

know

the

truth

is

the

opposite.”

For

example,

if

a

situation

is

going

disastrously

and

a

character

chirps,

“Well,

that’s

just

great,”

–

that’s

verbal

irony

(sarcasm’s

snarky

cousin).

In

satire,

you

might

praise

what

you

actually

want

to

attack,

or

appear

to

side

with

the

absurd

to

show

how

absurd

it

truly

is.

-

Dramatic

irony:

Sometimes

the

audience

is

in

on

a

truth

that

the

characters

or

narrator

pretend

not

to

know.

Jonathan

Swift’s

A

Modest

Proposal

is

dripping

with

dramatic

irony

–

readers

realize

the

proposal

is

horrifying,

but

the

narrator

blandly

carries

on

as

if

it’s

the

most

reasonable

solution,

thus

highlighting

the

real

horror:

society’s

indifference

to

the

suffering

of

the

poor. -

Sarcasm:

Sarcasm

is

a

more

blunt

form

of

irony

–

often

a

cutting,

mocking

remark.

In

moderation,

it

adds

bite.

E.g.,

writing

“Oh,

brilliant

idea,

Congress,

truly”

after

describing

a

particularly

boneheaded

policy

can

drive

the

point

home.

Just

be

careful:

sarcasm

is

like

hot

sauce,

a

little

can

spice

things

up,

but

too

much

overwhelms

the

dish. -

Situational

irony:

This

is

when

the

outcome

is

the

opposite

of

what

one

would

expect.

For

instance,

a

fire

station

burning

down

–

ironic!

A

satirical

piece

might

construct

an

ironic

scenario

to

make

a

point,

like

a

Nobel

Peace

Prize

winner

starting

a

bar

fight.

The

inherent

“that’s

not

supposed

to

happen!”

of

situational

irony

creates

a

comedic

twist

on

serious

matters.

Use

irony

as

your

ally

in

satire.

It

allows

you

to

illustrate

the

gap

between

how

things

are

and

how

they

should

be

in

a

powerful

way.

For

instance,

if

you

want

to

satirize

workplace

bureaucracy,

you

might

write

a

faux

memo

from

HR

that

cheerfully

announces,

“Due

to

our

commitment

to

efficiency,

all

employees

must

now

fill

out

17

forms

to

request

a

single

pen.”

The

irony

(efficiency

causing

inefficiency)

shines

a

spotlight

on

the

dysfunction.

Exaggeration

and

Hyperbole

When

in

doubt,

blow

it

out

of

proportion!

Exaggeration

(or

its

fancy

Greek

name

“hyperbole”)

means

taking

something

to

ridiculous

extremes

to

reveal

its

ridiculousness.

If

reality

is

mildly

absurd,

your

satirical

version

of

it

should

be

absurd

on

steroids.

This

technique

is

everywhere

in

satire

–

from

Swift

suggesting

baby-eating,

to

modern

satirists

joking

that

a

minor

tech

glitch

caused

the

apocalypse.

-

Caricature:

In

political

cartoons,

artists

draw

huge

heads

or

wild

features

–

that’s

exaggeration

in

visual

form.

In

writing,

you

can

“caricature”

a

behavior

or

idea.

Suppose

you’re

satirizing

celebrity

vanity

–

you

might

exaggerate

it

by

creating

a

character

who

hires

paparazzi

to

follow

him

to

the

fridge

so

even

his

midnight

snack

is

documented

by

the

press.

Over-the-top?

Exactly

–

that’s

the

point. -

Outrageous

analogies:

Compare

the

situation

to

something

absurdly

out

of

scale.

For

example,

“My

boss

treats

missing

a

deadline

like

it’s

the

end

of

the

universe

–

I’m

pretty

sure

he’d

schedule

a

public

execution

if

our

team’s

report

came

in

10

minutes

late.”

The

humor

in

the

overstatement

highlights

the

boss’s

overreaction. -

Taking

a

logical

premise

to

illogical

extremes:

Start

with

a

real

issue

and

keep

asking

“what’s

the

worst

that

could

happen?”

then

answer

it

in

a

ridiculously

literal

way.

Are

people

worried

about

government

surveillance?

Satire

it

by

imagining

dental

drones

that

fly

into

our

bathrooms

to

ensure

we

floss

–

for

our

health,

of

course.

Concerned

about

consumerism?

Write

a

story

where

people

sell

their

own

memories

to

afford

the

newest

smartphone.

By

amplifying

the

absurdity,

you

spotlight

the

underlying

issue

in

a

memorable

way.

Exaggeration

works

because

it

makes

the

implicit

flaws

impossible

to

ignore.

It’s

as

if

you’re

drawing

a

doodle

around

a

problem

with

a

big

red

arrow

saying,

“Look

how

crazy

this

is

when

taken

to

the

extreme!”

If

someone

says,

“You’re

exaggerating,”

as

a

critique,

the

proper

satirist

response

is,

“Exactly.”

😉

The

key

is

to

ensure

your

audience

gets

that

the

exaggeration

is

intentional.

You

usually

do

this

by

pushing

far

enough

that

it’s

clearly

not

meant

to

be

taken

literally

(e.g.,

no

one

actually

thinks

drones

will

enforce

flossing…

we

hope).

Parody

and

Imitation

Parody

is

the

art

of

mimicking

a

style

or

genre

to

poke

fun

at

it.

If

you’ve

ever

seen

a

Weird

Al

Yankovic

music

spoof

or

a

sketch

where

a

comedian

impersonates

a

politician’s

mannerisms,

you

know

the

power

of

parody.

In

writing,

parody

means

taking

the

familiar

format

of

something

–

a

news

article,

a

scientific

report,

a

poem,

a

speech

–

and

filling

it

with

absurd

content

that

highlights

the

original’s

flaws

or

the

absurdity

of

the

subject.

-

Style

imitation:

Suppose

you

want

to

satirize

sensationalist

journalism.

You

might

write

a

parody

news

article

with

the

breathless

tone

of

clickbait

journalism:

“Shock

Report:

Local

Man

Loses

Sock,

Blames

Government

–

You

Won’t

Believe

What

Happened

Next!”

The

structure

and

tone

mirror

real

news,

but

the

content

(a

lost

sock

treated

like

Watergate)

makes

it

funny

and

pointed. -

Borrowed

formats:

Common

parody

targets

include

academic

papers,

press

releases,

letters,

and

ads.

For

example,

The

Onion

once

parodied

those

heartfelt

charity

sponsorship

ads

with

a

piece

like,

“For

just

$5,000

a

day,

you

can

sponsor

a

politician.”

By

copying

the

earnest

style

of

charity

appeals

and

applying

it

to

greedy

politicians,

the

satire

comes

through

loud

and

clear. -

Literary

or

pop

culture

parody:

You

can

also

parody

specific

works

or

genres.

Writing

a

fairy

tale

in

the

style

of

a

corporate

memo,

or

a

Shakespearean

soliloquy

about

online

dating

–

the

fun

lies

in

the

mismatch

between

style

and

subject.

If

the

audience

knows

the

original

source

or

genre,

they’ll

appreciate

the

clever

twists.

Just

ensure

there’s

a

purpose

beyond

mimicry

–

parody

for

parody’s

sake

can

be

funny,

but

in

satire,

you

usually

use

it

to

critique

something

(e.g.,

parody

a

famous

speech

to

show

how

current

leaders

fall

short

of

past

ideals).

Parody

is

powerful

because

it

leverages

something

already

recognizable.

It’s

essentially

an

inside

joke

with

the

audience

–

“You

know

how

this

usually

goes,

right?

Now

watch

me

twist

it.”

When

done

well,

your

readers

will

both

laugh

at

the

imitation

and

realize

the

commentary

you’re

making

on

the

original

or

on

whatever

subject

you’ve

plugged

into

that

style.

Plus,

parody

can

lend

your

satire

a

sense

of

authenticity

–

a

faux

academic

study

format,

if

written

pitch-perfect,

can

almost

sound

legit,

which

only

heightens

the

humor

when

the

content

goes

off

the

rails.

Absurdity

and

the

Totally

Ridiculous

Sometimes,

the

best

way

to

highlight

reality’s

insanity

is

to

embrace

pure

absurdity.

Absurdity

in

satire

means

things

happen

that

are

wildly

illogical,

surreal,

or

just

jaw-droppingly

silly

–

yet

they

often

metaphorically

relate

to

a

truth.

This

overlaps

with

exaggeration,

but

absurdity

can

also

mean

the

humor

comes

from

nonsense

or

bizarreness

that

slyly

parallels

real

issues.

-

Absurd

characters:

Create

people

or

entities

that

are

one

step

beyond

reality.

Maybe

a

government

ministry

run

entirely

by

actual

clowns

(literally,

with

red

noses

and

big

shoes)

to

represent

how

you

view

a

real

policy

as

clownish.

Or

a

CEO

who

communicates

only

through

emojis.

The

key

is

the

character’s

absurd

trait

is

symbolic

of

a

real

trait

–

the

clown

ministers

=

foolish

leaders;

the

emoji

CEO

=

inarticulate

or

childish

communication

styles

in

corporate

culture. -

Illogical

worlds:

Satire

lets

you

imagine

a

world

that

operates

by

twisted

rules.

Catch-22

by

Joseph

Heller

is

a

classic

example:

a

military

rule

that

you’re

insane

if

you

willingly

fly

dangerous

missions,

but

if

you

ask

not

to

fly

them

you’re

sane

(so

you

have

to

fly)

–

an

absurd

bureaucratic

logic

that

satirizes

real

military

bureaucracy.

You

can

create

a

fictional

scenario

that’s

patently

ridiculous

to

shine

a

light

on

a

system’s

failings.

For

instance,

satirize

complex

tax

codes

by

having

a

scene

where

two

accountants

need

a

ouija

board

and

a

quantum

physicist

to

file

a

simple

tax

return

–

exaggeration,

yes,

but

also

absurd

in

a

Monty

Python

way. -

Deadpan

absurdity:

One

delicious

approach

is

to

present

absurd

statements

in

a

matter-of-fact,

deadpan

tone.

Imagine

writing,

“According

to

a

new

study,

0%

of

people

enjoy

being

stuck

in

traffic,

shocking

experts

worldwide.”

The

content

is

obvious

or

silly,

but

if

you

deliver

it

with

a

straight

face

(like

a

real

report),

it

tickles

the

reader’s

sense

of

the

absurd.

This

technique

often

leaves

the

audience

with

that

“Did

they

really

just

say

that?”

moment

–

perfect

for

a

chuckle

and

a

thought

about

whatever

you’re

actually

implying

(in

this

case,

maybe

how

some

studies

tell

us

what

we

already

know).

Absurdity

in

satire

often

borders

on

the

surreal,

but

it

should

connect

to

reality

by

a

thread

of

logic

or

analogy.

It’s

the

difference

between

a

random

non-sequitur

and

a

pointed

non-sequitur.

Random:

“Then

aliens

turned

everyone

into

sandwiches,

haha!”

(Okay…

weird,

but

what’s

the

point?).

Pointed:

“In

the

end,

the

committee’s

circular

logic

effectively

turned

the

debate

into

a

sandwich

–

lots

of

layers,

no

substance.”

(Weird

image,

but

conveys

a

critique.)

Aim

for

the

latter:

nonsense

that

means

something.

Understatement

and

Euphemism

On

the

flip

side

of

exaggeration

lies

understatement

–

another

satirical

tool.

Sometimes

describing

a

horrendous

or

extreme

situation

as

if

it

were

no

big

deal

can

be

ironically

powerful

(and

darkly

funny).

Similarly,

using

polite

or

technical

euphemisms

to

describe

something

outrageous

can

highlight

just

how

outrageous

it

is.

-

Understatement:

This

is

classic

in

British

satire

(the

Monty

Python

sketch

where

a

character

has

lost

all

his

limbs

and

calls

it

“just

a

flesh

wound”

comes

to

mind).

If

a

politician

tells

a

huge

blatant

lie,

a

satirist

might

dryly

comment,

“He

may

have

taken

a

slight

liberty

with

the

facts.”

The

discrepancy

between

the

reality

and

the

mild

description

creates

irony.

It

can

also

underscore

how

people

try

to

downplay

wrongdoing.

Understate

a

big

problem

and

you’ll

actually

draw

attention

to

its

magnitude. -

Euphemism:

Imagine

a

satirical

news

brief

about

an

authoritarian

regime:

“The

government

has

been

engaging

in

some

light

voter

persuasion”

(translation:

voter

intimidation).

By

using

gentle

terms

for

a

rough

action,

you

mock

the

euphemistic

language

officials

often

use.

It’s

a

way

to

indirectly

call

them

out

–

the

reader

reads

between

the

lines. -

Formal,

bland

tone

for

crazy

content:

Another

form

of

understatement

is

to

maintain

a

very

formal,

bureaucratic

tone

while

describing

absurd

or

horrible

things.

The

contrast

can

be

comedic

gold.

Example:

“Company

Memo:

We

regret

to

inform

employees

that

due

to

budget

cuts,

your

lunches

will

now

consist

of

literally

nothing.

We

appreciate

your

understanding

and

continued

starvation.”

The

prim

corporate

phrasing

of

an

outrageous

policy

(making

people

starve)

satirizes,

say,

corporate

cold-heartedness.

Understatement

works

particularly

well

when

the

real-life

phenomenon

you’re

targeting

involves

people

downplaying

something

important

or

failing

to

react

appropriately.

By

mirroring

that

dynamic,

you

highlight

it.

It’s

subtle

–

the

opposite

of

hyperbole’s

shout,

understatement

is

a

whisper

–

but

that

subtlety

itself

can

be

humorous,

as

if

you’re

conspiratorially

nudging

the

reader:

“This

is

insane,

but

shall

we

pretend

it’s

fine?

wink”

Other

Devices:

Satire

Spice

Mix

There

are

plenty

of

other

literary

spices

you

can

sprinkle:

invective

(sharp,

insult-driven

language)

can

add

heat,

though

use

it

wisely

or

it

just

becomes

a

rant.

Juxtaposition

–

placing

two

contrasting

elements

side

by

side

–

is

great

for

highlighting

absurd

contrasts

(e.g.,

a

millionaire

complaining

about

the

price

of

a

latte

next

to

a

report

on

poverty

rates).

Wordplay

and

puns

can

add

a

lighter

comedic

touch

between

heavier

barbs.

Allegory

(whole

stories

that

parallel

real

events,

like

Orwell’s

animals

on

a

farm

to

represent

a

revolution)

can

deepen

satire

but

require

careful

execution

so

readers

catch

the

parallels.

The

bottom

line:

mix

and

match

techniques

to

suit

your

piece.

One

satire

may

lean

heavily

on

irony

and

understatement

(dry

wit),

another

on

absurd

exaggeration

(silly

shock

value).

As

you

practice,

you’ll

develop

a

sense

of

which

tool

to

pull

out

for

which

job.

And

like

any

DIY

project,

having

a

full

toolbox

at

your

disposal

is

half

the

battle.

Crafting

a

Satirical

Piece

Step-by-Step

Alright,

time

to

roll

up

your

sleeves

and

actually

write

this

thing.

Staring

at

a

blank

page

can

be

intimidating

(as

intimidating

as

a

politician

at

a

truth-telling

contest).

But

fear

not

–

here’s

a

step-by-step

approach

to

go

from

a

vague

idea

to

a

polished

satirical

piece.

We’ll

break

it

down

into

manageable

steps:

Step

1:

Choose

a

Target

(Focus

Your

Premise)

Every

satire

needs

a

target

–

the

issue,

person,

or

behavior

you’re

making

fun

of.

Start

by

picking

something

that

you

care

about

or

find

absurd.

Your

genuine

irritation

or

passion

will

fuel

the

humor.

It

could

be

a

big

social

issue

(like

political

corruption,

climate

denial,

inequality)

or

a

petty

everyday

annoyance

(like

people

who

never

update

their

software

but

complain

their

phone

is

slow).

Nothing

is

too

grand

or

too

small,

as

long

as

there’s

something

worth

ridiculing.

However,

one

golden

rule:

punch

up,

not

down.

Choose

a

target

that

has

some

power,

influence,

or

choice

in

the

matter.

Satire

works

best

when

it

challenges

the

powerful

or

critiques

widely-held

follies,

not

when

it

mocks

the

vulnerable.

For

example,

satirizing

a

government

policy

or

a

billionaire’s

quirks

can

be

great;

satirizing

homeless

people

or

disaster

victims

–

not

so

much

(that

veers

into

cruel,

not

clever).

We’ll

talk

more

about

this

in

the

ethics

section,

but

keep

it

in

mind

from

the

get-go.

Aim

your

comedic

arrows

at

the

right

bullseye.

Once

you

have

a

broad

target,

narrow

it

to

a

specific

premise

or

angle.

“Government

incompetence”

is

too

broad

to

be

funny

on

its

own

–

but

“the

government

program

that

spent

$2

million

to

develop

a

ketchup

bottle”

is

specific

and

ripe

for

satire.

A

good

satirical

premise

is

crystal

clear.

You

(and

eventually

your

reader)

should

be

able

to

answer:

What

exactly

am

I

satirizing?

Is

it

a

particular

event,

a

type

of

person,

a

trend?

Jonathan

Swift

didn’t

just

satirize

British

policy

generally;

his

premise

was

specifically

ridiculing

the

heartless

attitude

of

the

English

wealthy

toward

poor

Irish

families.

From

that

clear

premise

sprang

the

“eat

babies”

idea.

Try

writing

your

premise

in

a

straightforward

sentence

first:

“I

want

to

satirize

__

because

__.”

For

example,

“I

want

to

satirize

corporate

PR

speak

because

it’s

absurd

how

companies

spin

bad

news

as

good.”

That

clarity

will

keep

you

on

track

as

you

add

layers

of

humor.

Step

2:

Find

the

Absurdity

and

Choose

Your

Satirical

Angle

Now

that

you

have

a

target,

ask:

“What’s

inherently

absurd

or

ironic

here?”

Your

job

is

to

amplify

that.

There

are

a

couple

of

ways

to

hone

in

on

your

satirical

angle:

-

Identify

the

contradictions

or

hypocrisy:

Is

there

a

gap

between

what

this

person/organization

says

and

what

they

do?

Between

the

ideal

and

reality?

For

instance,

if

your

target

is

“reality

TV,”

the

inherent

irony

is

that

it’s

often

scripted

and

fake.

Boom,

angle:

treat

the

fakeness

of

“reality”

with

extreme

seriousness,

or

flip

it

so

real

life

starts

having

confession

cams

and

dramatic

music.

Find

the

lie

or

the

flaw

and

shine

a

spotlight. -

Ask

“What

if…?”

questions

to

push

the

idea.

What

if

this

truth

was

taken

to

the

extreme?

(Exaggeration

angle.)

What

if

the

opposite

was

true?

(Irony

angle.)

What

if

I

present

it

in

a

different

format

or

context?

(Parody

angle.)

For

example:

What

if

a

tech

company

literally

started

worshipping

an

AI

as

its

god?

(Absurd

extreme

to

satirize

tech

obsession.)

Or

what

if

I

wrote

about

my

messy

roommate

as

if

he

were

a

historic

plague?

(Parody,

comparing

crumbs

to

locusts,

etc.) -

Find

a

fresh

perspective:

Sometimes

taking

an

unexpected

point

of

view

opens

up

comedy.

Could

you

tell

the

story

from

the

standpoint

of

an

inanimate

object

or

an

unlikely

character?

E.g.,

satirize

smartphone

addiction

with

a

piece

from

the

perspective

of

a

lonely

neglected

book

on

the

shelf,

witnessing

humans

worshipping

their

phones.

The

angle

becomes

the

personification

of

the

book

lamenting

like

an

old

spurned

friend.

This

indirect

approach

can

be

both

funny

and

poignant.

Brainstorm

freely

here.

Jot

down

as

many

absurd

ideas

or

analogies

as

you

can

related

to

your

topic.

Don’t

worry

if

they’re

too

crazy

–

sometimes

the

craziest

idea,

toned

down

just

a

notch,

becomes

the

perfect

satirical

hook.

Let’s

say

our

target

is

over-the-top

wedding

culture

(people

spending

ludicrous

amounts

on

weddings).

Absurd

brainstorm:

wedding

as

military

arms

race,

bride

and

groom

as

rival

generals?

Or

a

reality

show

“Wedding

Wars”

where

couples

compete

to

one-up

each

other?

Or

an

open

letter

from

the

future

child

(“Thanks

for

blowing

my

college

fund

on

a

chocolate

fountain,

Mom

and

Dad!”).

Notice

how

each

of

those

angles

highlights

the

original

absurdity

(weddings

that

have

lost

all

sense

of

proportion)

through

a

different

lens.

Choose

the

angle

that

makes

you

smirk

the

most

or

that

best

highlights

the

core

issue.

If

you’re

torn,

ask

which

idea

would

be

clearest

to

your

audience.

Remember,

clarity

is

key

–

your

readers

should

quickly

“get”

what

you’re

spoofing

once

they

start

reading.

If

the

connection

is

too

murky,

consider

sharpening

or

simplifying

the

concept.

Step

3:

Choose

a

Format

or

Structure

Satire

can

take

many

forms

–

and

picking

the

right

format

can

significantly

enhance

the

humor.

This

is

where

you

decide

how

you

will

present

your

satirical

idea.

Some

popular

structures

(which

we’ll

delve

into

in

the

next

section)

include:

a

faux

news

article,

a

satirical

op-ed

or

open

letter,

a

fictional

interview,

a

diary

entry,

a

user

manual,

an

advertisement,

a

listicle,

you

name

it.

Why

does

format

matter?

Because

form

can

itself

be

a

joke.

A

serious

format

(like

a

scientific

report

or

a

solemn

speech)

filled

with

ridiculous

content

creates

a

delightful

contrast.

For

example,

if

your

target

is

bureaucratic

inefficiency,

writing

your

piece

as

a

leaked

internal

memo

or

policy

proposal

could

amplify

the

satire

–

you’d

use

dry

office

lingo

to

describe

something

outrageously

dumb,

thereby

mocking

the

bureaucratic

tone

and

the

inefficiency.

Or

if

you’re

skewering

something

like

Instagram

culture,

maybe

write

it

as

a

step-by-step

how-to

guide

for

becoming

an

influencer

(highlighting

shallow

behaviors

through

the

faux

instructions).

Consider

your

audience

too.

Some

formats

are

more

instantly

relatable

to

certain

readers.

A

younger

online

audience

might

love

a

listicle

(“5

Signs

Your

Cat

is

Plotting

World

Domination”

–

a

silly

satirical

concept),

whereas

a

more

literary

audience

might

appreciate

a

short

story

or

essay

format.

Also,

different

formats

lend

themselves

to

different

strengths:

a

fake

news

article

is

great

for

deadpan

delivery

of

absurd

“facts,”

while

a

parody

letter

or

monologue

lets

you

dive

deep

into

a

character’s

voice.

Outline

the

structure

in

broad

strokes.

Will

it

have

sections

(like

a

news

article

with

headline,

body,

maybe

fake

quotes)?

Will

it

be

one

continuous

narrative?

Will

it

be

Q&A

style?

Having

this

blueprint

prevents

your

satire

from

becoming

a

rambling

blob

of

jokes.

It

gives

you

scaffolding

to

build

on.

If

you’re

not

sure,

a

straightforward

approach

is

to

write

it

as

a

satirical

essay

or

column

–

basically

you

speaking

in

ironic

tone

–

which

is

flexible

and

doesn’t

require

strict

formatting.

Once

you

pick

a

format,

stick

to

its

conventions

as

you

write

–

that’s

half

the

humor.

If

it’s

a

love

letter,

start

with

“Dear

so-and-so”

and

maybe

end

with

a

ridiculous

sign-off.

If

it’s

a

scientific

abstract,

include

an

“Introduction”

and

“Conclusion”

with

tongue-in-cheek

academic

jargon.

Committing

to

the

bit

sells

the

satire.

(Need

inspiration?

In

the

next

section,

we’ll

explore

common

satire

formats

like

news,

open

letters,

etc.,

with

examples.

Feel

free

to

skip

ahead,

then

come

back

here

to

continue

your

steps.)

Step

4:

Write

the

First

Draft

–

Be

Bold,

Then

Refine

Time

to

put

pen

to

paper

(or

fingers

to

keyboard)

and

let

it

rip.

Your

first

draft

is

the

place

to

go

big

with

your

humor

ideas.

Don’t

self-censor

too

much

at

this

stage

–

you’ve

done

your

planning,

now

let

the

satire

flow.

A

few

pointers

as

you

draft:

-

Adopt

the

right

tone/voice:

If

you’re

writing

in

a

persona

(e.g.,

a

clueless

official,

a

concerned

citizen,

a

talking

dog),

fully

inhabit

that

character’s

voice.

If

it’s

a

generic

narrator,

decide

if

they’re

naive,

sarcastic,

outraged,

or

eerily

calm

about

absurd

things.

Consistency

of

voice

makes

the

piece

feel

cohesive. -

Lead

strong:

The

opening

lines

should

signal

the

satirical

nature

and

grab

attention.

Often,

stating

the

absurd

premise

right

at

the

start

works

wonders.

Example:

“The

Department

of

Agriculture

announced

today

that

the

nation’s

cows

are

now

required

to

produce

10%

lactose-free

milk

by

2025,

to

accommodate

lactose-intolerant

Americans.”

That’s

a

goofy

premise

delivered

seriously

–

a

hook,

in

other

words.

It

sets

up

the

reader

for

the

style

of

jokes

to

come. -

Commit

to

the

bit:

Satire

often

works

best

when

it

doesn’t

blink.

Write

with

conviction

as

if

everything

you

say

is

logical

or

factual,

even

when

it’s

ridiculous.

The

humor

comes

from

the

contrast

between

the

serious

delivery

and

the

insane

content.

A

common

mistake

is

winking

too

hard

at

the

audience,

e.g.,

breaking

character

to

say

“just

kidding.”

Trust

your

readers

to

get

it

(with

a

clear

premise

and

tone,

they

will). -

Sprinkle

a

variety

of

humor:

Use

the

toolkit

–

irony,

exaggeration,

etc.

–

but

don’t

use

everything

at

once,

and

don’t

beat

one

joke

to

death.

Maybe

your

piece

mainly

uses

exaggeration,

but

you

toss

in

a

clever

ironic

twist

or

a

parody

reference

here

and

there

for

flavor.

Running

gags

(a

repeated

joke

or

callback)

can

also

be

fun,

but

ensure

they

escalate

or

vary

so

it

stays

funny.

For

example,

if

in

a

satirical

article

you

refer

to

a

hapless

politician

as

having

the

brainpower

of

a

toaster

in

paragraph

one,

maybe

in

paragraph

three

the

toaster

is

actually

making

better

decisions

in

a

side-by-side

comparison.

In

short,

mix

up

your

comedic

attacks:

a

surprise

analogy

here,

a

deadpan

absurd

statement

there,

maybe

a

pun

or

witty

wordplay

when

appropriate. -

Keep

it

tight

(especially

with

humor):

Brevity

is

the

soul

of

wit!

In

a

first

draft

you

might

write

long,

which

is

fine,

but

be

prepared

to

trim.

Jokes

often

land

better

when

they’re

not

belabored.

For

instance,

instead

of

rambling

on

to

explain

why

something

is

funny,

let

the

scenario

or

dialog

itself

carry

the

humor

and

then

cut

to

the

next

point.

Trust

the

audience

to

fill

in

one

plus

one

=

haha.

Don’t

worry

if

at

this

stage

some

lines

feel

more

silly

than

satirical

or

vice

versa.

The

first

draft

might

be

rough

or

too

over-the-top

–

that’s

okay.

It’s

easier

to

tone

down

excess

than

to

add

in

spark

later.

Get

your

ideas

on

the

page.

You

might

end

up

with

a

piece

that

has

a

hilarious

middle

but

a

weak

ending,

or

a

great

concept

but

some

flat

jokes

–

all

fixable

in

the

next

step.

Step

5:

Revise

and

Polish

(Sharpen

that

Satire)

Now

for

the

unsexy

(but

crucial)

part:

editing.

Great

satire

often

comes

out

of

great

editing

–

refining

the

balance

between

humor

and

message.

Step

away

from

your

draft

for

a

bit

if

you

can,

then

come

back

with

fresh

eyes

and

maybe

a

red

pen

(or

the

delete

key).

What

to

look

for

while

revising:

-

Clarity

check:

Will

a

reader

not

inside

your

head

understand

the

target

and

premise?

Make

sure

the

setup

in

the

beginning

makes

it

clear

what

you’re

satirizing.

You

might

need

to

tweak

the

introduction

or

add

a

hint

if

it’s

too

oblique.

If

you

gave

it

to

a

friend,

could

they

“get

it”

by

the

first

few

sentences

or

headline?

If

not,

clarify

your

premise. -

Consistency

of

tone:

Did

you

accidentally

drop

out

of

character

or

slip

from

satirical

into

just

factual

or

preachy?

Ensure

the

satirical

voice

stays

consistent.

If

you

find

a

paragraph

that

reads

like

a

straight

essay

or,

alternatively,

one

that

feels

like

a

different

style

of

humor,

smooth

it

out

to

match

the

rest.

Consistency

makes

the

piece

feel

professionally

done

rather

than

patchy. -

Timing

and

flow

of

jokes:

Check

the

pacing.

Does

the

piece

build

up

to

a

good

climax

or

final

punchline?

Many

satirical

pieces

save

the

sharpest

zinger

for

the

end,

leaving

the

reader

with

a

final

“Ouch!”

(in

a

good

way).

Make

sure

the

best

stuff

isn’t

buried

in

the

middle

and

the

ending

isn’t

a

fizzle.

You

might

rearrange

sentences

or

paragraphs

for

better

setup-payoff

structure.

Also,

remove

any

joke

that

doesn’t

serve

a

purpose.

Sometimes

we

write

a

funny

line

that

we

love,

but

if

it

sidetracks

from

the

main

point

or

confuses

the

tone,

it

may

need

to

go.

Kill

your

darlings,

as

they

say

–

or

at

least

maim

them

until

they

behave. -

Is

it

actually

funny?

This

sounds

obvious,

but

when

you’ve

re-read

your

piece

10

times,

you

might

become

numb

to

the

humor.

Try

reading

it

aloud.

The

parts

where

you

naturally

smile

or

giggle

are

keepers.

The

parts

where

even

you

are

bored

–

those

need

punching

up

or

cutting.

If

you

can,

have

someone

else

read

it

and

see

where

they

laugh

or

look

puzzled.

(Choose

an

honest

friend,

not

just

your

mom

who

says

everything

you

do

is

brilliant.) -

Balance

critique

vs.

humor:

Ensure

your

criticism

isn’t

completely

lost

in

the

jokes,

nor

the

humor

drowned

out

by

soapboxing.

Satire

is

a

balancing

act.

If

upon

rereading,

the

piece

feels

too

mean

or

angry

without

enough

wit,

lighten

it

up

with

a

bit

more

silliness

or

charm

in

the

narrator’s

voice.

Conversely,

if

it’s

giggle-worthy

but

not

actually

making

any

point,

you

might

sharpen

a

line

or

two

to

drive

the

message

home

more.

The

best

satire

often

lets

the

absurd

scenario

imply

the

criticism,

without

lecturing

–

but

a

slight

nudge

or

hint

at

the

real

point,

especially

towards

the

end,

can

help

land

the

message.

For

instance,

ending

Stephen

Colbert-style

with,

“…and

that’s

how

we’ll

solve

everything,

because

what

could

possibly

go

wrong?”

–

a

final

irony

that

winks

at

the

reader

to

not

take

it

at

face

value.

Proofread

for

the

usual

suspects:

grammar,

spelling,

and

in

this

genre

especially,

word

choice.

Using

a

hilariously

wrong

word

or

a

malapropism

can

be

a

joke,

but

make

sure

it’s

intentional.

Often,

precise

wording

makes

the

difference

in

a

joke’s

setup

or

punchline.

Also

confirm

any

factual

elements

you

included

(satire

often

includes

real

references

or

names):

nothing

kills

a

great

gag

like

discovering

you

got

a

basic

fact

wrong

(unless

your

narrator

is

intentionally

getting

it

wrong

as

part

of

the

satire

–

that

can

be

a

joke

too,

but

it

should

be

on

purpose).

Lastly,

come

up

with

a

good

title

or

headline.

If

you

haven’t

already,

craft

one

that

teases

the

premise.

In

satirical

news,

the

headline

is

half

the

joke

(“Study

Reveals:

Babies

Are

Stupid”

still

makes

us

laugh).

In

an

essay

format,

a

witty

title

helps

grab

attention

(e.g.,

“An

Open

Letter

to

My

Roomba,

Regarding

Its

Plot

to

Kill

Me”).

Make

sure

it

matches

the

tone

of

the

piece

–

absurd

title

for

an

absurd

piece,

or

a

dry,

blandly

serious

title

for

a

piece

with

deadpan

delivery

(sometimes

funnier

that

way).

Congratulations

–

you’ve

now

got

a

satirical

piece

ready

to

hit

the

presses

(or

at

least

your

blog/social

media/Microsoft

Word

file).

But

before

you

publish

or

share

it

widely,

let’s

arm

you

with

knowledge

of

different

formats

you

can

experiment

with,

and

a

heads-up

on

ethics

and

pitfalls.

After

all,

with

great

power

(to

mock)

comes

great

responsibility

(to

not

be

a

jerk).

Common

Satire

Formats

and

Structures

Satire

isn’t

one-size-fits-all.

The

format

you

choose

is

part

of

the

joke.

Let’s

explore

some

popular

structures

for

satirical

writing,

with

examples

of

how

each

works.

You

can

use

these

as

inspiration

or

templates

for

your

own

pieces:

free

“The

SpinTaxi”

newspaper

box

on

a

Washington

DC

street.

The

Spintaxi’s

deadpan

news

parody

format

is

so

iconic

that

its

logo

alone

signals

you’re

in

for

a

satirical

read.

News

Parody

(Fake

News

Articles)

One

of

the

most

prevalent

forms

of